Chapters

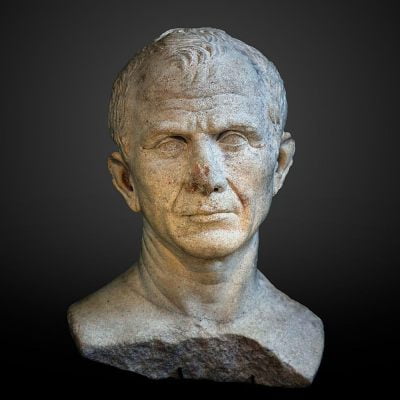

Gaius Julius Caesar was born on 12 July 100 BCE (according to Mommsen and Dio, he was born on 13 July and gained his fame thanks to the governorship in Gaul).

Son of Gaius Julius Caesar the Elder, whose political career was not impressive and Aurelia Cotta. He got his father’s name.

One of the members of the populares, is related to Cinna and Marius. After their death, he held successively the offices of quaestor, aedile, praetor, consul and dictator. He gained fame thanks to his exile in Gaul and thanks to the help of his soldiers he managed to overcome the opposition, focused on the Senate and Pompey, and then, after many years of fighting, take over the full power in Rome. Murdered during the Ides of March by senators led by Marcus Brutus and Gaius Cassius. Before his death, he adopted Gaius Octavian in his last will, designating him as his heir.

Adolescence

We do not know much about Caesar’s childhood because ancient historians were not interested in the lives of children who were not idealized like adults. Various legends were disseminated about his childhood. One of them says that Caesar was to be born thanks to a Cesarean section (hence the name), but it is rather a modern invention because in the past such a procedure was performed only in the case of a woman’s death during childbirth, while Caesar’s mother, Aurelia Cotta died in 54 BCE. His father was Gaius Julius Caesar the Elder, after whom he inherited the names.

Caesar was the nephew of Julia – wife of Marius, leader of the Populares in Rome. This party, which forced changes in the State, was in a disadvantageous position since in 82 BCE Sulla was a dictator in Rome, the leader of the conservative party – the Optimates.

The struggle between these parties also touched Caesar. At the age of sixteen, in 84 BCE, he received – thanks to Marius – the first political and religious office – the title of the priest of the god Jupiter (flamen Dialis). However, just in 82 BCE, he lost it because he had refused to follow the order of Sulla, who imposed a divorce on him with Cornelia. She was the daughter of Lucius Cornelius Cinna, the second leader of the Populares after Gaius Marius. Caesar also lost Cornelia’s dowry, but Sulla guaranteed him inviolability.

Caesar, however, did not believe Sulla, who had previously broken his promise and he fled in a hurry to the mountains. There he hid among swamps and forests. The inconvenience of these hiding places caused him a serious illness. When he was transported on a stretcher to another place, he was captured by Sulla’s army. A large ransom paid to the soldiers allowed Caesar to save his life and freedom. His acquaintances in Rome, the relatives of Aurelia, and even the Vestal Virgins, but above all, liked by Sulla, Aurelius Cotta, pleaded for Caesar to enable him to return safely to Rome. Caesar, however, had no intention of returning to Rome – he knew that in such an inconvenient political situation in which he found himself, his political career was doomed to failure. He also knew that as a politician, he had to show up in the army and fight beforehand.

In the year 80 BCE Caesar went to north-west Asia Minor, where he assisted Marcus Minucius Termus in the siege of the city Mytilene on the island of Lesbos, where he was entrusted with the mission of bringing ships from the king of Bithynia Nicomedes IV. He did this mission very well, he even managed to make friends with the king, which later became a stigma in his political career in Rome. It has been suggested many times (probably rightly) that they became lovers. It is difficult, however, to infer Caesar’s bisexuals. This episode stemmed rather from the decadent style of Nicomedes’ court, which probably captivated the young Roman.

After the mission, Caesar returned to Bithynia under the pretext of conducting court cases. Rumours about Caesar’s alleged connection became stronger when, before his death, Nicomedes enrolled his kingdom in Rome. In 74 BCE the Roman Senate transformed Bithynia into a Roman province.

In the war campaign itself, Caesar showed his fortitude in conquering the city, for which he was awarded the so-called corona civica, which was awarded to those who saved the battle of Roman citizens. Since then, the senators had to get up when the young Caesar entered the Senate.

After the military mission, he did not return to Rome, where Sulla still ruled. He moved to the fleet of Publics Servilius Vatia Isauricus in Cilicia, whereas an officer he campaigned against numerous pirates who had their seats in the mountainous regions of this land.

Sulla’s death in 79 BCE started a new period of struggles. Caesar realized that it was too early to take power from the Optimates. They were still the dominant political party, gathering in their circle the majority of important leaders. Caesar decided to gain popularity with his very good rhetorical skills and management. To this end, he sued Gnaeus Dolabella in 77 BCE, a former consul, for abuse and extortion committed while in power in the province of Macedonia. This person was chosen not by accident – as an adherent of the deceased Sulla he was a political opponent of Caesar, and he was supported by the province’s population. However, Dolabella, thanks mainly to the connections, won the case.

Caesar gained so much that more cities and provinces asked him to sue. And this was the case in 76 BCE when Gaius Antonius, who plundered many Greek cities during Sulla’s reign was sued by Caesar. This case was won by Antony, who, although he did not end up in prison, lost morally, Caesar was again popular. Similar cases took place in Rome itself. Additionally, in order to gain popularity, he organized numerous feasts and parties for people. He did all this to gain favour and more friends.

In 75 BCE, when travelling to Rhodes to study with Apollonius Molon, Caesar was kidnapped by pirates. He stayed with his crew among the robbers, while sending his servants to Greece to collect the ransom. The famous anecdote of Suetonius has survived. Caesar, kidnapped by the pirates, strenuously protested against the ransom of 50 silver talents, as too low. He threatened the pirates, which was perceived rather as a joke. However, after being freed from the ransom, Caesar gathered hostile Greeks and took revenge, returning to the camp of his recent oppressors and killing them all.

The first serious political activities

In 74 BCE Caesar made the decision to go to Bithynia attacked by the king of Pontus Mithridates VI. Despite the lack of experience and appropriate command functions, he managed to gather all scattered Roman troops around, and even volunteers, and hit unexpectedly the enemy army, which withdrew, leaving the threat to the Roman state.

During his stay in the East, he was informed about the death of his uncle Aurelius Cotta, who held office in the college of pontificates. It was a priesthood office that was in charge of religious matters, which could indirectly influence policy. He was informed that he was to replace his relative. Year 73 BCE is considered the beginning of Caesar’s mature political career.

About 68 BCE Caesar became quaestor of the province Hispanic Ulterior, thanks to which he could sit in the senate. The quaestor’s position was not satisfactory for Caesar because he was only popular in his province. That same year, Caesar married Pompeia, the granddaughter of Sulla himself. At that time, he had many lovers, but he was closer to those who could help him both in his political career and in providing information.

After marriage to Pompeia, he was appointed curator of the Via Appia road leading from Rome to Brundisium. It was a seemingly secondary office, but in fact quite influential. This position was used by Caesar to acclaim the gratitude and respect of travellers through good administration along this path. He spent a large sum of money for the good performance of the function entrusted to him, and he became dependent on Marcus Crassus, from whom he often borrowed large sums of money. During this period, Crassus was the richest Roman in the republic.

In 65 BCE Caesar was elected curule aedile. His main task since then was watching over the order and construction in Rome, and above all, the organization of the games. At the same time, he showed extravagance, exposing a large number of gladiators to demonstrations of fights, thus wanting to win over the people.

In the year 63 BCE, he received, after the deceased Lucius Metellus Pius, the dignity of PontifexMaximus, or the high priest. Pontifex Maximus exercised supremacy over the whole religious life in Rome, but also had serious political influence, consisting mainly of the right to determine the list of senatorial families. Caesar has spent a large sum to buy the voices of the people and gain this position.

This year he exposed Catiline’s conspiracy, in which the aforementioned Catiline sought lese-majesty. Catiline was finally captured and brought to trial. During the trial, most senators were for the death penalty for the conspirators. Caesar, on the other hand, declared that punishing death without a trial, especially for people who were well-known and merited to the state and distinguished families, would be unjust and incompatible with Roman customs. He stated that a better solution would be to imprison them in various parts of the empire. Ultimately, however, suspicions by the senators about his involvement in the plot forced Caesar to withdraw from the case.

In 61 BCE Caesar once again went to Hispania Ulterior, this time as praetor. There, he also took an armed action against the previously unrivalled mountain tribes. At first, Caesar occupied most of the villages, but when the fleeing population took refuge in the surrounding island, Caesar made a rather unfortunate decision. He ordered to build rafts, on which soldiers had to get to this island. As a result of the outflow, which consumed the majority of the unit, as well as the resistance that was put on the rest of the island, only one soldier survived the entire campaign and came back to swim. It was only after a week that ships arrived from Gades, on which the Romans reached the island and killed starving refugees. Then Caesar sailed towards the city of Brigantium, which surrendered without a fight. In general, the whole campaign in Hispania was received positively, the empire gained quite large territories, and Caesar was proclaimed an emperor. He also did well as a provincial administrator: he tried to pay as much as possible from the provinces, but also forbade the creditors to hold more than two-thirds of the debtor’s property.

In the same year (61 BCE) Caesar was acclaimed imperator, which gave him the right to triumph in Rome. The problem, however, was that he wanted to submit his candidacy as a consul for 59 BCE, and as an army commander (according to tradition) he had to wait outside the gates of the city for the Senate’s permission to enter the city. Caesar wanted to use the possibility of submitting the candidacy in absentia, but this possibility was successfully blocked by Marcus Porcius Cato. With a choice – to give up triumph or consul’s title, Caesar resigned from the first.

The First Triumvirate

Soon after returning to Rome, in 60 BCE, Caesar signed the first triumvirate, a secret agreement with the consuls Gnaeus Pompey and Marcus Licinius Crassus, thanks to which he was elected a consul for 59 BCE. Pompey was dominant in the deal, with a large political base and Crassus with an equally large financial base, while Caesar, due to its popularity among the people and the army, was only the executor of their decisions.

As consul, Caesar immediately undertook one of the most important reforms – the agrarian reform. The basic change was the ban on compulsory land purchase, without the owner’s consent. It was also possible to fill the ground, first promised to the distinguished veterans of Pompey. The reform met with opposition in the Senate, but Caesar finally managed to push through the reform with the help of the other two triumvirs.

Another political idea of Caesar was the elimination of Cicero from the political scene. To this end, Caesar chose Clodius for the tribune. Clodius was rather uninteresting, which threatened the demise of Caesar’s authority among the people. In particular, he was in an incestuous relationship with his sister and was well known for his religious profanation, but Caesar needed to get rid of Cicero, which Clodius did. He passed as a tribune a popular law condemning the exile of anyone who committed murder without a court order. Of course, this bill hit the Cicero, who sentenced the participants of Catiline’s conspiracy to death. Cicero was expelled and his property stolen by Clodius. Caesar got rid of his next long-time opponent.

At the same time as these important events, a lot happened in Caesar’s private life. Pompey, who had previously had an affair with Caesar’s mistress, was offered the hand of his daughter, Julia, although she was already engaged to Servilius Caepio. This marriage strengthened the political ties between Pompey and Caesar, although his motive was probably also Pompey’s strong affection for Julia. Caesar himself married Calpurnia, the daughter of Piso, whom he guaranteed the consul’s position.

In Rome, it was already known that three politicians were ruling, who passed other laws. One of them was granting him, for five years, the governorship in Cisalpine Gaul and Illyria with the border on the Rubicon and Transalpine Gaul. Especially the latter tempted Caesar with the possibilities of running war campaigns he needed so much, and also getting money.

Caesar in Gaul

Caesar went to Geneva in March 58 BCE in order to organize an armed action against the Helvetians there. They did not directly threaten the Roman state, but they were a good excuse for him to get fame. As it turned out, as a result of the military campaign, Caesar managed to conquer today’s France. The fights lasted until 53 BCE when the enemy was defeated.

In the meantime, in 56 BCE in Lucca, there was a congress of triumvirs and many other influential people. Caesar called upon his former political collaborators because he feared whether the alliance would survive, because in Rome there was a discord between Crassus and Pompey, who, fearing for his position, began cooperating with the Optimates, even allowing Cicero’s return to Rome. This situation was so dangerous for Caesar that his political opponents made demands for the removal of Caesar’s laws and for his removal from Gaul. Caesar, Crassus and Pompey agreed on dividing the influence in the Republic – they received the consulate, and Caesar extended the command in Gaul for five years and got a considerable sum of money. Caesar thus assured himself of the favour of the triumvirs, as well as his old provinces – that is, the field for military-political and administrative displays.

The prolongation of Caesar’s governors in Gaul provoked uneasiness in Brittany, then inhabited by Veneti. They began to suspect that in the near future Caesar would plan invasions of their land. They formed a fairly large coalition of Germanic tribes, which began to threaten the security of the Republic.

The imprisonment of Caesar’s deputies by the Veneti gave him a direct excuse to initiate a war. He issued an order to build a fleet whose command he entrusted to Decimus Brutus, and he took command of the land forces himself. However, the decisive fight took place at sea. After the victory, he took revenge on the deputies’ imprisonment – he ordered the murder of all the elders of the Veneti, and attacked the allies of the Veneti, to deter other tribes from doing so.

A similar fate was met in 54 and 53 BCE. Britons who, though not without difficulty, were beaten. This campaign, however, did not bring many profits – the Britons were not a wealthy tribe, and the losses that Caesar suffered as a result of the fighting surpassed the spoils. The only success of Caesar was the fact that he was the first to cross Roman troops across the English Channel and for a long time effectively discouraged them from interfering in political affairs on the continent.

After returning to Gaul, he heard about the death of his daughter, Pompey’s wife, Julia, which ultimately broke up the friendly relations between them.

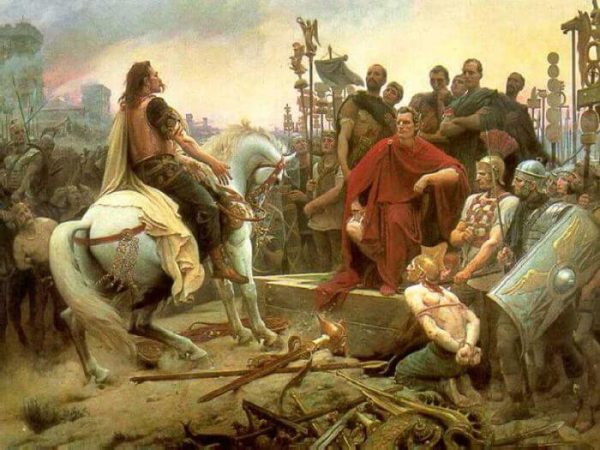

The situation in the Roman state and the weakening of their political position of Caesar led to the rebellion in Gaul in 53 BCE. The uprising was managed by Vercingetorix. According to Plutarch, Caesar decided to gather all available armies and, contrary to the principles of martial art, immediately set out to face the enemy. The energetic action and the element of surprise caused Caesar to succeed. (description of Vercingetorix’s uprising)

Defeating Vercingetorix did not end the uprising. At the beginning of the year 51 BCE, he had to fight the Biturgigs. Caesar, however, like the members of the Gallic alliance, did not treat them severely, demanding only ransom and a few slaves. The last conflict, the capture of the city of Uxellodunum, however, ended very brutally, cutting off all the rebels of the hands, wanting to perpetuate the power of Rome, but also to let the Gauls know how high the price of disloyalty is.

During this campaign, Caesar introduced many innovations to the army. He improved the art of siege, including the psychological use of some siege devices, which Caesar considered to be of little use from a purely tactical point of view, but useful to cause panic in the ranks of the enemy. He created a reserve ride and doubled its pay.

In the summer of 53 BCE, Caesar learned about the death of Crassus. The triumvirate stopped existing definitively. Caesar did not succeed in renewing family relationships with Pompey, who married the widow of Crassus. In Rome itself there was anarchy at the time, so the Senate gave Pompey a single consular office, which had not happened before. Caesar took advantage of this situation, demanding his ally to create the possibility of standing for the office of a consul in absentia.

Civil war

At the beginning of the year 50 BCE, the office of Caesar’s governorship in his provinces expired. Out of fear of his political position and the possibility of degrading to the rank of an ordinary Roman citizen he wanted to take the office of a consul, but the laws prepared by Pompey himself stood in the way. The first of them introduced a mandatory period of five years between the office in Rome and the governor’s office. The second demanded him to appear in Rome if he was willing to submit his candidacy to the consul’s office. The situation was exacerbated by the fact that the political opponents in Rome had already tried to find a successor for Caesar’s office in Gaul, and Pompey demanded from his former ally to return two legions, which the Senate had given to him during the fights with the Gauls.

Description of the Civil War

The Civil war of Julius Caesar with Pompey the Great decided about the fall of the Republic and the rise of the Empire.

Caesar had to do something not to lose everything he had achieved so far. He took advantage of his great fortune, which he obtained during his governorship to bribe Pompey’s political supporters who were in a difficult financial situation. Pompey, however, called himself the defender of the Republic and the Senate and won the favour of most of the senatorial families who were afraid of Caesar’s power. At the end of his governorship, he reduced the tribute in Gaul and did not interfere in their internal affairs, which assured him of their favour in the future. He paid out large sums for the fight in Gaul to the devoted soldiers.

In Rome, he did not lack opponents – the Senate dismissed Caesar from the governorship, and deprived him of the possibility of applying for the office of the consul in absentia. Caesar’s messengers sent to Rome were sent back to the Senate. This fact was used by Caesar to persuade his soldiers to accept the military coup in Rome.

Presumably on 10 January 49 BCE Caesar crossed the Italian border on the Rubicon River, he said the famous words alea iacta est, meaning “the die has been cast”. Crossing this border at the head of the army was already a public opposition to the legal power of the Senate, from which there was no turning back. The civil war (bellum civile) lasted several years.

Caesar’s first move was to take Ariminum. There was panic in Rome, everyone remembered the slaughter in the days of Gaius Marius and there was a belief that now it will be. Caesar himself did not encounter any resistance on his way and he easily gained the city of Corfinium, and he sent free Domitius Ahenobarbus who was defending the city. Caesar officially proclaimed that he was defending the Republic and the office of the tribunes before the collusion of the senate houses on behalf of the Roman people. Completely surprised by the turn of events, Pompey and his senators left Italy, and Caesar entered Rome. He immediately opened the treasury and obtained the money needed for further war campaigns. He went to Spain to deal with Pompey’s supporters who could threaten his further actions in the East.

On Caesar’s road stood the city of Marseilles, which did not want to speak on his side. Initially, he took part in the siege, but after some time he headed the small branch to Spain. He defeated the army of Afranius and Petreus there, but he did not punish the defeated, and he only ordered to the dissolution of their army. In August and September of 49 BCE, Caesar took Hispania Ulterior and Marseille he won without a fight.

After returning to Rome in December 49 BCE he was announced dictator by the intimidated and deposed Senate. He allowed the return to his homeland of people expelled during Sulla’s time, he lifted people’s debt, and restored rights to offices. He held the dictator’s function for only 11 days, assuring himself a consul’s election the following year.

Caesar, knowing that he had no advantage at sea, decided to surprise Pompei, who had been in Greece since his assumption of power in Rome. He quickly gathered seven legions and, without a specially large escort of warships, crossed over to the territory of today’s Albany. From January to July 48 BCE lasted Caesar’s attempts as he was in a worse position, being cut off from all supplies.

After the arrival of the long-awaited reinforcements led by Mark Antony, Caesar decided to try to beat Pompey. It came to the battle of Dyrrachium, in which Pompey’s army broke Caesar’s army, putting him in great danger. Only Pompey’s mistake saved Caesar from the final catastrophe. Labienus, Pompey’s supporter and former commander of Caesar, lost all captured prisoners.

Facing enormous losses and supply difficulties, Caesar decided to retreat east to the forthcoming army of Quintus Metellus Scipio, to strengthen Pompey’s forces. Caesar founded a camp on the hill above the Enipeus River next to Pharsalus. Caesar was followed by Pompey, who was accused of being afraid of Caesar’s supporters.

Finally, at Pharsalus on 9 August 48 BCE there was a decisive battle between Caesar and Pompey, where Caesar, thanks to his tactics, luck and Pompey’s mistakes, managed to defeat the enemy forces.

After the battle Caesar gave freedom to all prisoners who pledged not to resurrect him and the higher officers gained the right to preserve property. Caesar, in this way, wanted to avoid being compared to Sulla’s murders or to Gaius Marius. He demanded from those people only that they promise not to join Pompey and, at the same time, generously bestowed all those who decided to change the front. This strategy meant that most of the senators eventually moved to Caesar’s camp, and Pompey could no longer proclaim that he was the defender of the Republic and the Senate.

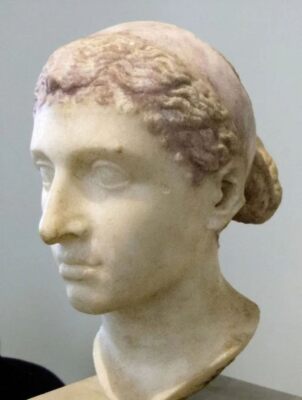

Pompey, after losing the battle, fled to Egypt, where he was insidiously murdered at the behest of the 14-year-old King Ptolemy XIII, who feared for his influence on Egyptian politics and the conflict with Rome. When Caesar landed in Alexandria, he got the head of the dead Pompey. Legend says that seeing the defeated enemy, Caesar did not show joy, on the contrary, he cried and put a kiss on Pompey’s forehead. In Egypt, there was a civil war between the heirs of the throne, a juvenile Ptolemy XIV and his older sister, Cleopatra, exiled from Alexandria. Caesar allied himself with Cleopatra, who became his lover and gave him his only biological son – Ptolemy Caesarion. It was quite dangerous because for a long time Caesar was only a guest in the palaces of Alexandria, surrounded by an incited crowd. With the help of Caesar, Cleopatra obtained the Egyptian crown after the short Alexandrian war, which ended by the Romans in 47 BCE.

On his way back to Rome, in 47 BCE, Caesar defeated the rebellious King of Pontus in Asia Minor, Pharnaces II in the battle of Zela, and after the victory, ending the expedition, he sent a message to the Senate with the words: veni, vidi, vici or “I came, I saw, I conquered”.

Then he dealt with the remnants of the Pompeians in Africa led by Cato and Scipio in the battle of Tapsus on 6 April 46 BCE.

Independent rule and reforms

After his victory over Pompey, Caesar could finally afford to triumph in Rome alone in the summer of 46 BCE. It was a great celebration of his victories in Gaul, Egypt, Pontus and Africa. There were a few days of feasts, games and tournaments, Caesar himself, in order to gain the favour of the people, generously gave all of the spoils of war.

Taking advantage of the fact that no one could effectively endanger his power, he carried out numerous reforms to raise the state from anarchy and long-lasting wars. They also included the Roman provinces, contributing to the integration of the empire. He initiated, among others romanization of external provinces through major resettlements from Italy to veterans of wars and the Roman proletariat, mainly to Gaul, Asia Minor and Africa. He established a new gold coin – aureus, and in 46 BCE, as Pontifex Maximus, he carried out the reform of the calendar with the help of the Alexandrian astronomer Sosigenes, thus creating the Julian calendar.

Literary achievements |

In addition to speeches, poetry and dramas not preserved to our times, Caesar wrote two famous historical monographs, which enter the so-called Corpus Caesarianum:

Caesar’s authorship of the following is questionable:

He was also the author of De analogia, dedicated to Cicero, and pamphlets against Cato entitled Anticatones. These two have not survived to our times. |

During his reign, the following buildings were erected in Rome for the first time: a marble temple, a triumphal arch and dome constructions. The land reform was completed, the provincial governor was banned for more than two years, associations that might have contributed to conspiracies were dissolved. In practice, Caesar became the ruler of Rome, and the Senate became a façade institution. Its number was enlarged to the number of 900 senators, through the edict of Caesar, raising several hundred equites’ families to the status of nobilitas. Thanks to this, Caesar’s supporters gained a definite and permanent advantage in the Senate, although the old senate families still tried to oppose him. Unlike Sulla, Caesar did not murder or denounce his opponents by preaching the principle of clementia. He did not take revenge on his former political opponents, even withdrawing the confiscation of property.

However, despite positive reforms, Caesar was quickly hated by the old aristocracy for showing almost complete contempt for the old republican institutions. Although he formally tried to maintain the appearance of the legality of his power, his actual decisions led to an almost complete disintegration of the old system of government (distribution of offices contrary to existing laws).

After settling matters in Rome, Caesar finally killed the followers of the late Pompey. In November 46 BCE Caesar, already as consul, went to Spain to finally deal with his only opponents, the sons of Pompey – Sextus Pompey and Gnaeus Pompey. The battle took place on 17 March 45 BCE at Munda in which Caesar’s army, despite the enemy’s advantage, defeated the Pompeians.

Assassination

After the battle of Munda, no one was able to threaten Caesar. On 14 February 44 BCE the Senate proclaimed Caesar the perpetual dictator (dictator in perpetuum), the high priest, emperor and “father of the fatherland.” They tried to proclaim him the king of Rome, but Caesar refused, because this function was hated by the people since the times of Tarquin, moreover Caesar still tried to preserve the appearance of republican legality.

At that time, the leader of Caesar’s opposition was Gaius Cassius Longinus and Marcus Iunius Brutus. They were bound earlier to Pompey’s camp and after the defeat at Pharsalus, they surrendered to Caesar, but still, they showed their reluctance towards him.

Caesar was warned about the possibility of assassination. However, he always approached this with a detachment, claiming that he would live all the time in fear if the bodyguard would still surround him. At the same time, he was sure that no one would dare to do the coup because it would trigger another civil war.

At that time, Caesar was planning a trip to the East against hostile Parthians, which was due to begin on 18 March 44 BCE.

Description of the assassination

At the head of the conspiracy for the life of Julius Caesar stood Gaius Cassius Longinus and Marcus Iunius Brutus.

On the day of the conspiracy, Caesar almost did not thwart his assassins’ plans. His wife begged him to stay at home, because nightmares were tormenting her that night. Caesar, although reluctantly, wanted to accept her requests, but the visiting envoy of the assassins persuaded him to go to the Senate’s deliberations.

At the last session of the Senate on 15 March 44 BCE on the Ides of March, Caesar took his place in a gold-plated chair. Tillius Cimber came up to him, asking for the grace for his exiled brother, and other initiators began to follow him. Caesar, irritated by this insistence, tried to get up, but then Cimber took his toga, which was to be an agreed sign for all to attack. The first blow was made by Servilius Casca, but the blow was too weak. Caesar repaid him with a blow to the shoulder, but then they fell on him giving 23 blows with daggers.

The last blow, inflicted by the hand of Brutus, whom Caesar considered a friend, turned out to be deadly. Julius Caesar, seeing Brutus, was to shout in Greek: “And you, child?”, Which could be either a threat or a regret. A widely used version: “And you, Brutus?” (Et tu, Brute?) Is a figment of Shakespeare.

As it turned out later, Caesar named Octavian, the grandson of his sister, Julia, his principal heir.

He died on 15 March 44 BCE stabbed at the foot of the statue of Pompey, his former supporter and enemy. A few days later, he was cremated on the Roman forum. A few ancient sources describing this event have survived, but certainly, the closest to reality is the work of

Suetonius, who witnessed it.

Description of Caesar’s funeral

Caesar did not manage to complete the plans for the conquest of the Dacians and Parthians, and, as he expected, his death caused another civil war, in which his former leader Antony fought with Octavian.

Caesar’s ambitious plans before death

Marriage, offspring and mistresses |

MARRIAGES:

LOVER

ADOPTED

|